No matter how bad the Soviet system was, it’s part of our past. A destruction of the related forms and images cannot and will not erase it.

Nini Palavandishvili: Soviet Modernist Architecture 2019, p. 12

The article series "Georgian Perspectives" provides insights and analyses of contemporary Georgian social life from a geographical viewpoint. This means that all articles examine the social space and the practices taking place within it. This includes both the built space and the non-built space and all communications about places and spaces. It is important to underline that the insights given here must always include views from the outside, as the author is neither a native speaker nor permanently living in Georgia.

Monumental decorative art from Soviet Georgia

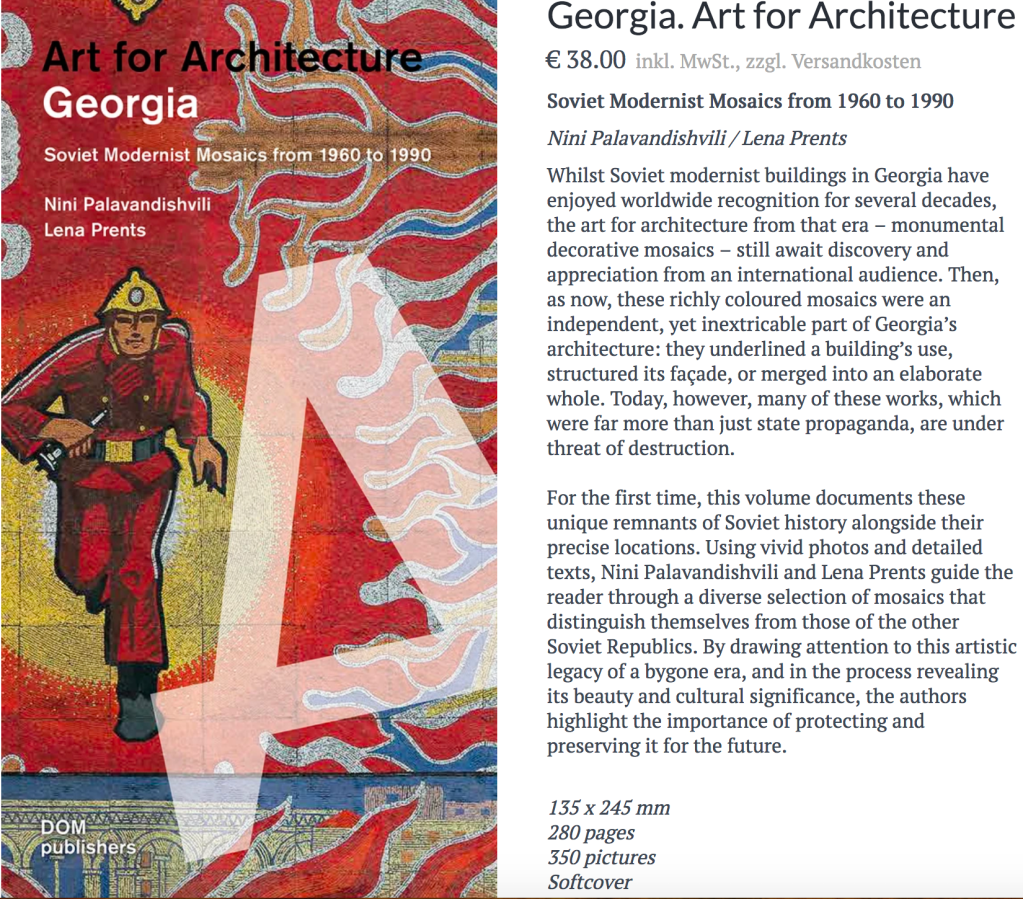

In their book „Art for Architecture. Georgia. Soviet Modernist Mosaics from 1960 to 1990“, the two authors Nini Palavandishvili and Lena Prents argue that monumental-decorative art had a special significance and character on the territory of the former Georgian Soviet Republic. There, as in other former Soviet republics, the monumental mosaics are found mainly on public buildings such as sports facilities, administrative buildings, universities and industrial plants. However, they are also to be found inside buildings such as large reading rooms of libraries and canteens of universities and schools. According to Nini Palavandishvili, one of the special points about these mosaics is that in Georgia, Soviet symbols such as the hammer and sickle and people like Stalin and Lenin are almost never depicted. The works of the Georgian artist Zurab Tsereteli in the health resort of Pizunda represent „probably the most complex mosaic-decorated territory in the former Soviet Union“ (Nini Palavandishvili 2019, p. 7).

Reasons for the decay of the objects of art

Today, most of the mosaic works from the Soviet era are decaying. Many are already lost, according to Nini Palavandishvili. This has its cause in three circumstances. The fundamental problem is the overall economic situation of the Georgian state, which is still desolate today. The 1990s were marked by civil war, wars of separation and the decay of industrial enterprises and state institutions. At that time, „survival was Georgia’s main concern“ (Nini Palavandishvili 2019, p. 6). Existing works of art were dismantled, stolen and sold, many decayed without anyone being interested in their preservation. Many of the monumental mosaics are located at former educational and health care facilities such as spa hotels, health clinics and sports halls, which have been inhabited by internally displaced persons since the early 1990s. Just as the Georgian state has not yet succeeded in creating adequate housing for the IDPs, it has not been able to invest in the preservation of the building fabric (cf. Applis 2020).

„Lost spaces“ – industrial architecture on the road from Kutaisi to Sugdidi

„Unfortunately, there is no great interest in its preservation in the broader sense, neither on the part of art and architectural historians nor in public.

Nini Palavandishvili, 2019, p. 6

Former sanatoria „Aia“ in the spa town of Tskatubo

Decaying front of a workers‘ housing block in Poti

With the wave of privatization since the late 1990s and the increasing liberalization of the economy since 2005, more and more previously public buildings and apartment blocks came under private ownership. Nini Palavandishvili (2019, p. 7) identifies this as the second reason for the increase in damage since the new owners were mostly uninterested in art. They see their preservation instead as a burden, although „these works were often created by the outstanding artists of that time“ (Palavandishvili 2019, p. 7).

Third, with the Saakashvili government since 2005, an active turning away from Soviet history began. From then on, the Soviet era was interpreted as a history of colonisation, and this was also associated with a turning away from Russia as the political successor to the Soviet Union. In contrast, the government turned to Europe and the USA as its most important partners. In 2011, the Georgian parliament adopted the so-called ‚Freedom Charter‘, which included a ban on all communist totalitarian symbols. As already mentioned, this ban had little effect on the monumental mosaics, as the only thing that could be found there was a CSSR written in Cyrillic letters, which could easily be removed if necessary. Nevertheless, turning away from Russia has an impact on the question of whether the works of art, which should be explicitly understood politically, are to be preserved or removed. After all, the monumental-decorative art of the sixties to the eighties deals primarily with propaganda themes such as ‚friendship among nations‘, ‚victory of the proletariat in the struggle for socialism‘ and ‚industrialisation and urbanisation‘ (cf. Nini Palavandishvili 2019, p. 6). Particularly affected by these developments, which of course represent a necessary emancipatory process of the citizens of Georgia, was the monument to the ‚Treaty of Georgiyevsk‘ in Gudauri.

This monument was intended to celebrate the friendship between Russia and Georgia. Still, it was not mentioned by the Soviet media after its inauguration in 1983, according to the research of Nini Palavandishvili (see Nini Palavandishvili & Lena Prents 2019, p. 222). The reason for this, according to one of the artists, Nodar Malasonia, was that he and his colleagues Zurab Kapanadze and Zurab Meshawa had decided to portray both nations equally. The nationalities can be recognized by their costumes, motifs from fairy tales, epics and typical buildings and everyday scenes. For Georgia, topics and figures were chosen that are strongly connected with the struggle for freedom and national self-confidence. There are depictions of Saint George, of Amiran and of Queen Tamara. The central mother figure, however, bears clear Christian connotations due to its proximity to the Virgin Mary. Thus one finds a number of reasons which may have led to the fact that „the big brother might have been offended“ (Nini Palavandishvili & Lena Prents 2019, p. 222). This openness to interpretation may also have led a group of activists to successfully work for the preservation and restoration of the monument on the road to Stepanzminda.

History of mosaics in Georgia

In her inventory of the mosaics of Soviet modernism, Nini Palavandishvili explains that the artistic influence of the Muralismo movement as a revolutionary movement in Mexico (1910-1920) was of fundamental importance for the Soviet Artists‘ Association in general and Georgia in particular. However, it was only after the death of Nikita Khrushchev that this influence could develop. In 1955, he had issued a decree prohibiting the use of any uneconomical building decoration. During the Brezhnev era (1964-1982), the state was the largest client, and in 1983 the Faculty of Monumental Decorative Art was founded in Tbilisi as part of the State Academy of Art. Nini Palavandishvili attributes the special significance of mosaic art in Soviet-era Georgia to the fact that it has historical roots in the region that can be traced back to the 2nd century AD (for examples see in detail Nini Palavandishvili 2019, p. 9).

Georgia experienced a series of dramatic caesura in the 20th century, whose consequences for the self-understanding of the country's population are grave. 1918 was the year of the declaration of independence from Russia. However, the Democratic Republic of Georgia only existed until the occupation by the Red Army in 1921 and Georgia was incorporated into the Soviet Union as the Georgian SSR. In 1991, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Georgia again declared independence, followed by wars of secession in Abkhazia and South Ossetia with a total of 150,000 people forcibly displaced. After the Russian-Georgian war in 2008, Russia recognized Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent states from Georgia. It is therefore not surprising that the relationship with Russia in today's Georgia is strongly addressed from the perspective of colonial oppression. Thus, the path through a city leads deep into the present and past of the people living there. By discovering objects und spaces, one can learn much about what is constitutive for peoples’ lives.

The authors Nini Palavandishvili and Lena Prents want to show, in their treatment of the monumental mosaic art, that many of the mosaics were not just functional art or simple propagandistic Soviet art. Some of them also have an emancipatory character, because they extensively depict Georgian folk national motifs, topoi and figures.

Text: © Stefan Applis (2020)

Photography: © Stefan Applis (2017, 2018, 2019)

References

Applis, S. (2020): New Perspectives for Tskaltubo. Caucasusedition. Journal of Conflict Transformation. 1 July 2020.

Palavandishvili, N. & Prents, L. (2019): Art for Architecture. Georgia. Soviet Modernis Mosaics from 1960 to 1990. DOM publishers. Berlin.

Websites with further examples of monumental-decorative mosaic art of the Soviet Union

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/preserving-ukraine-soviet-history-mosaics

https://www.disegnodaily.com/article/mosaics-of-the-former-ussr

https://osnovypublishing.com/en/decommunized-ukrainian-soviet-mosaics/