Georgia was the host country of the International Tourism Fair in Berlin in 2023. The country presented itself under the motto „infinite hospitality“. At the same time, the capital, Tbilisi, promoted itself with the slogan „Balcony of Europe“. Before the pandemic, over 9 million tourists traveled to Georgia in 2019 – the country has a population of around 3.9 million. Tourism collapsed during the coronavirus period but recovered in 2022 with around 5.5 million tourists, almost all visiting the old town of Tbilisi. What awaits visitors in an urban area that has undergone far-reaching restructuring since the 2000s with a view to hoped-for tourism development as a central development motive?

The architecture(s) of the Georgian capital

Tbilisi’s architecture is often described as hybrid. However, the city is less old than expected; the last time it was destroyed was around 200 years ago. Private houses are generally not older. Due to the multiple conquests from the historical neighbouring empires of Persia, Byzantium, Russia, Mongolia, etc., a diverse community developed in the city. The 19th century is represented by classicist and historicist buildings, followed from 1921 by Soviet architectural styles of Stalinist Historism, Constructivism and Brutalism. Since the 2000s, radical capitalist change has made hypermodern architecture possible, for which there seem to be no architectural limits (van Assche & Salukvadze 2013).

Anticipating the tourist gaze as a central motif of urban planning

The sociologist John Urry described the tourist gaze as a distanced experience of space, whereby the tourist as an actor becomes the trigger of specific spatial productions without participating in the local conditions that lie beyond the touristic surfaces. The built space with all its objects, such as buildings, streets, parks, etc., is capitalised. Cultural assets are thus used to feed consumption processes within the tourism industry. In the case of the Georgian capital, an entire section of the old city centre was recreated to position Tbilisi as a European old city between East and West („Balcony of Europe“), as a global tourist destination on the one hand and an investment destination for international investors on the other. These processes have only been taking place since around 2009. They can be traced as if in a laboratory, making Tbilisi extremely interesting for urban and tourism geography research.

The „New Life for Old Tbilisi“ programme

In 1999, the Georgian government applied for the Old Town to be included on the UNESCO World Heritage List. In 2001, however, UNESCO finally rejected the Georgian government’s application due to the need for standards for protecting historic buildings and the absence of a city or state management plan to preserve historic structures. In the opinion of many observers, the causes of the already far-reaching transformation in 2005 were primarily due to the endeavours of the local political and private elites to build a new city and implement new identity narratives that set themselves apart from the Soviet past. In the process, all central urban planning tasks were abandoned and handed over to the „invisible hand“, so to speak, against the backdrop of radical market liberalisation.

The „New Life for Old Tbilisi“ programme was launched in 2009 (see Angela Wheeler 2016). The consequence of this was a remodelling of the old town, essentially detached from the fundamental criteria of monument protection. This weakened the housing and living needs of particularly vulnerable groups. The programme’s target group was international cultural tourists, which is why the service sector was to be expanded and the traditionally high proportion of residential areas reduced. In addition, free space was to be created for property investors and providers in the hotel industry. On paper only, the aim was also to improve living conditions for the local population.

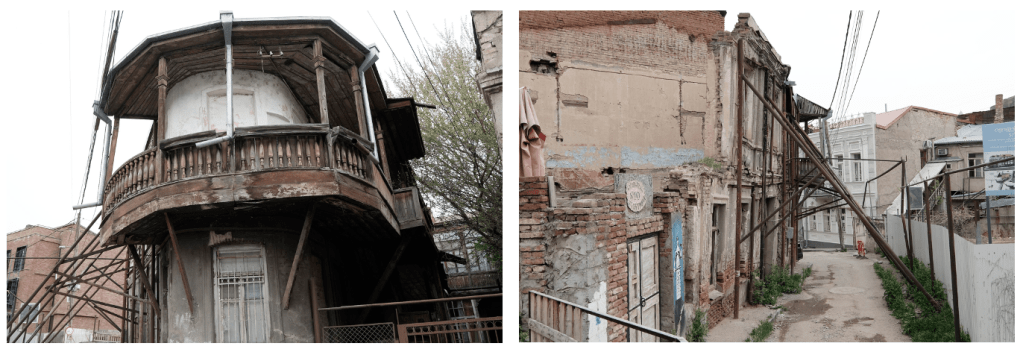

Historic vacant and dilapidated building stock in the centre (Applis 2022)

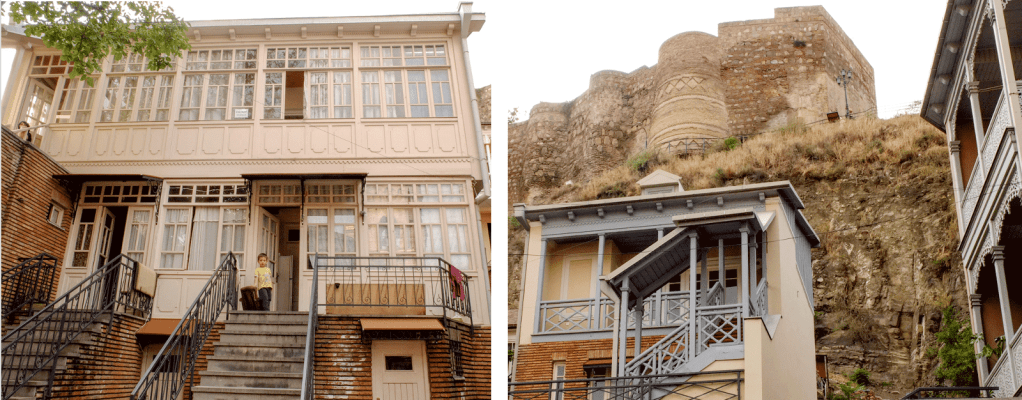

Reconstructions and interpretations after the renovation in the historic district (Applis 2017)

The structural consequences of the programme

The city guaranteed all loans from Georgian banks, and the redevelopers were given a free hand in negotiations with homeowners; after completion, the city bought back the buildings at a fixed price of $400/m2 if the redevelopers or homeowners wished. As a result, the pastel-coloured postcard view of the old town that tourists today consider historic was created. Not even the façades were often preserved, and new façades were invented in which the balconies were deemed authentic. The former inhabitants had previously been evicted and were hardly allowed to resettle. The forms of communication in divided courtyards typical of Tbilisi since the end of the 19th century and continued in the Soviet era were thus dissolved in the touristy old town. However, they still exist in the immediate neighbourhood, even if their dissolution also advances there.

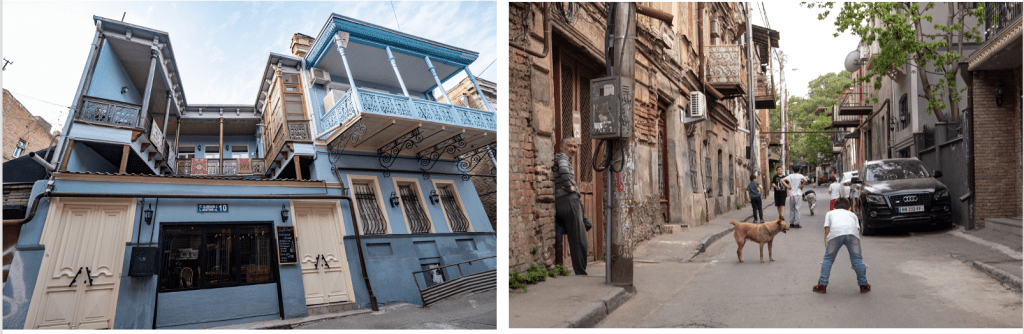

Left: A tourist accommodation whose architecture is pure fantasy; right: Children playing in the street in a neighbourhood that is still inhabited (Applis 2022)

Text: Stefan Applis (2024)

Photography: Stefan Applis (2017-2023)

Bibliography

Angela Wheeler (2016). New Look for Old Tbilisi: Preservation Planning in Tbilisi Historic District. Journal for Identity Studies in the Caucasus and the Black Sea Region. Vol. 6 (2016). https://ojs.iliauni.edu.ge/index.php/identitystudies/article/view/230

Kristof van Assche & Joseph Salukvadze (2013). Multiple transformations, coordination and public goods. Tbilisi and the search for planning as collective strategy. European Planning Studies. DOI: 10.1080/09654313.2022.2065878