The following text is an excerpt from the travel guide "Discovering Tusheti", which will be published by Mitteldeutscher Verlag Halle in 2024 and is jointly written by the ethnologist Florian Mühlfried and the geographer Stefan Applis. For the first time, a cultural and nature travel guide provides an almost complete description of the architecture of the villages in the high mountain region. The explanations are based on the work of various Georgian anthropologists and architects. The work of Sergi Makalatia (1893-1974), who worked in Tusheti and Chevsuretia in the 1920s and 1930s, takes first place. The architectural drawings in his book on Tusheti, published in 1933, are by Ucha Japaridze, Rene Schmerling, and Dawit Tsitsishvili. Close reference is also made to the work of Longinas Sumbadze (1948-2021), who, based on earlier expeditions to Tusheti in the 1974s, undertook a fundamental survey of the residential buildings and was supported by the photographic and drawing work of his son Nodar Sumbadze. In addition, drawings and sketches were used as the basis for the newly produced illustrations from the survey work 'Fortified Historical Settlements of Georgia in the Northern Highlands', published in 2018 only in Georgian and edited by Irine Elisbarashvili, Manana Suramelashvili, and Tsitsino Zschachkhunashvili; the latter collects older and current graphic representations of the architecture of Tusheti.

The settlement structure in the high mountains of Tusheti

Most fortified summer settlements in Tusheti were built on avalanche-proof, sun-exposed, rocky slopes, making it easier to defend the territory en masse in an attack. While in the so-called Free Svaneti, the villages, within which each family community had a fortified tower, were rather loosely organized, in the old villages of Tusheti, one can see throughout the attempt to build as compact a settlement as possible to evacuate women and children in the five- to six-storey buildings in the event of an attack. Their roofs have two forms – a stepped pyramidal structure (sipediani) made of stone, as found in the Pirikiti valleys, and a flat, single-sided roof made of wood, as seen in the valleys of Chaghma, Gometsari as well as Tsovata.

From the towers, they warned the population of the appearance of an enemy. The first floor was often used for prisoners in the towers; this narrow floor was only accessible from above. Children and women could hide on the middle floors, while the floors used for defence were those equipped with embrasures (satopuri). The last floor had a kind of stone canopy (called salode) from which stones could be thrown at the enemies. It was not uncommon for these defences to be surrounded by a high wall. During an enemy attack, people and goods were supposed to find refuge here. The Omalo, Indurta and Diklo fortresses all had high walls, of which some ruins remain. […] Based on the research of the architect Longinas Sumbadze, three types of houses are distinguished below, which can still be found in the mountains of Tushetia today.

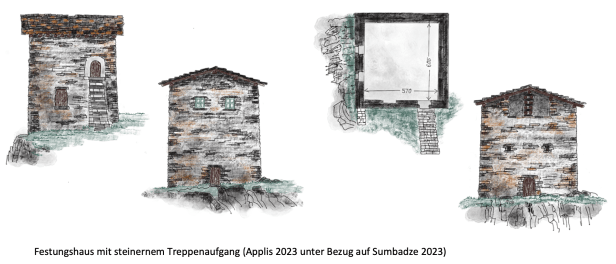

The Tusheti Fortress House

The fortress house does not reach the height of the defence towers. Like every building in Tusheti, it is constructed of layered clay slate, usually without mortar – the exception being the Pirikita fortified towers with their pyramid-shaped stepped roofs. The symmetrical high front façade of the fortress house faces the slope and thus frontally against approaching enemies. The thickness of the walls is 90-100 cm at the base and decreases to 60-65 cm towards the top. Because of the cold winters, the walls were plastered on the inside, and the animals spent the winter on the ground floor of the houses to use their body heat. They kept window openings narrow because of the winter cold and for defence reasons. […]

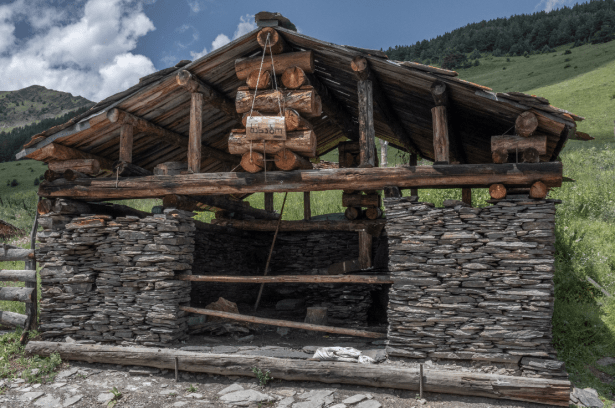

Some fortress houses have a partially open attic (tschercho) with a plinth supporting the roof, on which the ridge rests; others have oriels hanging high on the walls. The tschercho not only housed ammunition and weapons for defence but was often also equipped with a hatch-like roof covering the openings (tschardachi), from which stones could be thrown and boiling water poured on the enemy. Later, when constant defensive readiness for defence wasn’t necessary in more peaceful times, these attics were used as storage areas. […]

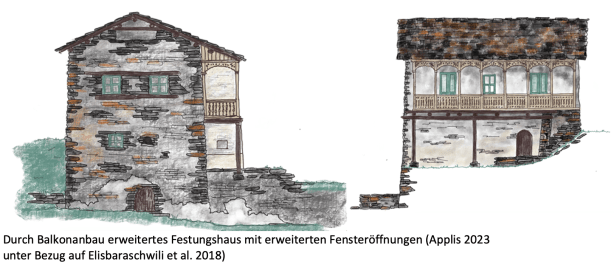

The transition house

The most important difference, according to Sumbadse, is that it had a real attic, which was not intended as a defensive platform but was used entirely for agricultural purposes, mainly for storing fodder for grain-fed livestock. Moreover, in these buildings, the ground floor was no longer used as a stable for the livestock but as a living or working area. Accordingly, people converted other buildings into pure stables. […] The most important features of this transitional house include:

- The replacement of the open hearth with a fireplace or an iron stove.

- The replacement of the narrow windows with larger, glazed windows in limited numbers.

- The division of the space into individual rooms.

- A balcony with a wooden railing over which a stone or wooden staircase connects the living room with the courtyard.

- The arrangement of wooden floors and plastered ceilings.

- The separation of the dwelling and the barn.

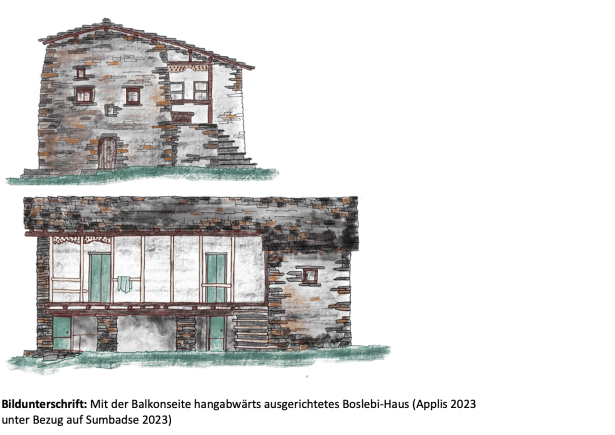

The Boseli House or Stable House

The third type of house identified by Lombadze is an elongated, two-storey, multi-room barn house with a gallery. It differs in many respects from the older homes. The house has been turned 90 degrees, stands horizontally on the slope, and has an elongated façade with a wooden gallery that defines the view of the building. This house’s window areas are larger, the façade is plastered, and the wooden balconies are often painted.

The ground floor of these houses is often used as a barn and for storing food and other supplies, although occasionally, there are also living quarters here. As a rule, however, these are on the first floor above. These houses are characteristic of the associated villages‘ winter settlements (boslebi) due to the new buildings and conversions that took place in peacetime. […]

The barn house

The barn house is the older and smaller variant of the house type that is widespread in the winter settlements and combines living and agricultural functions. The two-storey house-barn, in which no one lived in summer because the families moved to the higher-lying main settlements, was not intended for defence in the event of an enemy attack. The ground floor of this house was usually divided into two parts and served simultaneously to house the livestock in winter and to house family members, mainly the women. […]

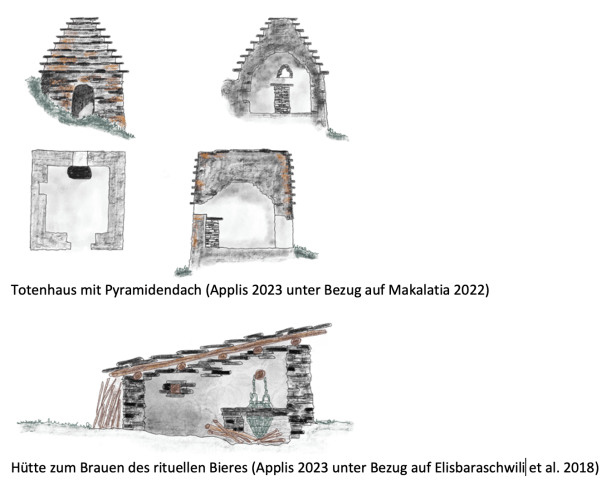

Religious architecture

In addition to residential and defensive structures in Tusheti villages, various religious forms can also be found near Tusheti settlements. On the one hand, communal graves (akldama) with two-sided slate roofs were built outside the villages, where the dead were laid to rest wrapped in simple shrouds (sudara). During the plague epidemic, sick people also sought out these houses to die there. The cult buildings also include the so-called shrines, which often consist of small towers piled up of slate slabs, in which flags and other cult objects were kept; next to the shrines, the horns of sacrificial animals are piled up, and men brew ritual beer to carry out the religious festivities – the corresponding beer huts are only accessible to men. […]

The travel guide "Discovering Tusheti", which will be published by Mitteldeutscher Verlag Halle in 2024, is the follow-up volume to the travel guide "Discovering Svaneti" published in 2021; both travel guides combine geographical and ethnographic perspectives based on the current state of research on the respective regions.

Text: (c) Stefan Applis (2023)

Drawings & Photography: (c) Stefan Applis (2023)

Reading recommendations:

Sergi Makalatia (2022). Tusheti. Folk Traditions. Artanuji Publishing. Georgien. Neuauflage des Buches von 1933. https://www.artanuji.ge/book.php?id=570

Longinaz Sumbadze (2023). Folk Architecture of the Caucasus: Tusheti. Edited by Nana Sumbadze, Nodar Sumbadze, Maya Sumbadze und Jesse Vogler. Georgien.

Hello! Will the Book about Tusheti be published in english?

LikeLike

Hi, first of all in German, but we are already looking for a publisher in Georgia to publish it in English as well. Best, Stefan

LikeLike

That sounds great!! I will be the first to buy the english version. Love Tusjeti which I have visited five times, both as a journalist and as a passionate hiker 😊

LikeGefällt 1 Person