The significance of the Alawerdi Monastery and the Alawerdoba Festival for the Georgian Orthodox Church

It is not only the collapse of the Soviet Union and Georgia’s independence that have led to a demarcation of the North Caucasus since 1991. The Georgian Orthodox Church also has an interest in demarcating the border region in the north, and thus Tusheti, from the south of the Russian Federation, which is characterised by the Islamic faith. The Georgian Orthodox Church plays a crucial role in Georgia’s politics and in defining what it means to be Georgian. It enjoys constitutional status and tax exemption in Georgia and receives state subsidies. The Catholicos-Patriarch is Illia II, the Archbishop of Mtskheta-Tbilisi. Since the end of the Soviet Union, the GOK has pursued the goal of pushing back non-orthodox, presumably pre-Christian practices in the mountain regions and defining and propagating the Christian faith according to its reading by building new churches, conducting processions and increasing its presence at religious festivals.

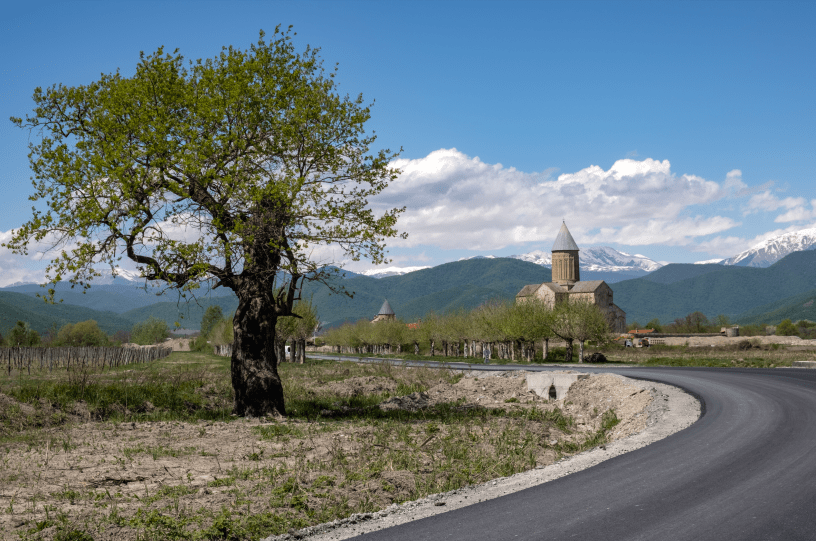

For example, in 2006 and 2007, icon processions were held for the first time in Tusheti along the border, led by Archbishop David, the Metropolitan of the Alaverdi Monastery located in the Alvani Valley, in order to spiritually demarcate the Christian space from the Islamic space. As part of these icon processions, four Orthodox churches built after the Tsarist takeover in 1801 were also visited to conduct services, weddings and baptisms. The Archbishop sees the strengthening of the Georgian Orthodox faith and the suppression of pre-Christian practices as a prerequisite for the revival of Tushetia, which in turn is a prerequisite for strengthening and protecting the region from its Islamic neighbours. To this end, a monastery is also to be built in the dilapidated fortress of Diklo near the border with Dagestan.

The Alaverdi Monastery dates back to a church complex from the 4th century. In the 11th century, the church was expanded and provided with a steeple, which was the largest of its kind in Georgia until the construction of the Trinity Church in Tbilisi in 2004.

Even today, the Alawerdi Church is the third largest church in Georgia. The name of the church is disputed. Some refer to a church founder named Joseph of Alawerdi (Ioseb Alawerdeli); for the bishop of the monastery, Metropolitan Davit, on the other hand, the name comes from a type of plant or refers to its neighbourhood to the village of Alvani (from alwnis gwerdse – literally: next to Alvani). The name Alawerdi is, however, still widespread in other regions of the South Caucasus, where it is usually traced back to the Islamic faith, more precisely to the Turkic-language allah verdi – God has given. And so there are indeed hints that the place might have had a special, perhaps even sacred, significance for Muslims as well. On the one hand, there is a rotunda-shaped structure in the churchyard, which probably dates from the time of the reign of the Persian-Muslim ruler Shah Abbas and is thought by some – probably mistakenly – to be a mosque. On the other hand, there is a legend, still widespread today, about a Muslim builder of the church who fell during the work and exclaimed: Allah verdi (in the sense of: God has made it so). According to the legend, the master builder left a handprint in the rock where he hit the ground. In fact, until the early 2000s, there was a handprint on the floor of the Alawerdi church, where some visitors would place their own hand and make a wish. However, this imprint was removed at the behest of Bishop Davit and is to be transferred to a museum, although this has not happened to date.

Another indication of the special significance of the place for both Christians and Muslims is the Alawerdoba festival, which for centuries has been held annually on three consecutive weekends in autumn next to (and during the Soviet period also in) the church. Formerly one of the largest folk festivals in Georgia, it was attended by both Christians and Muslims, as well as both highlanders and lowlanders, who celebrated and traded there. Around 2006, however, this festival was declared a purer church festival and measures were taken to discourage unpopular practices, including Muslim attendance.

Text: Florian Mühlfried (2023)

Photography: Stefan Applis (2023)